Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Session: Poster Session

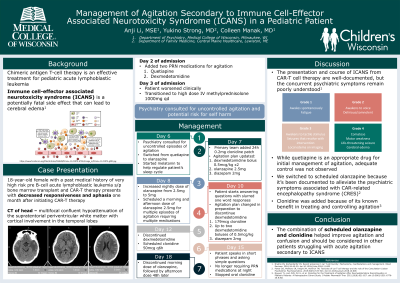

(029) Management of Agitation Secondary to Immune Cell-Effector Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS) in a Pediatric Patient

Trainee Involvement: Yes

Anji Li, MSE (she/her/hers)

Medical Student

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States- CM

Colleen K. Manak, MD

Assistant Professor

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

Introduction: Chimeric antigen T-cell therapy (CAR-T) is an effective treatment for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but it’s known to cause neurotoxicity that can lead to fatal cerebral edema, termed immune cell-effector associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) (1). Although standardized grading systems and treatments for ICANS have been documented (2), the role of a consultation-liaison psychiatrist in treating the residual neuropsychiatric symptoms is less clearly detailed.

Case Description: An 18 y.o. female with a history of high-risk pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, s/p bone marrow transplant and CAR T-cell therapy presented with decreased responsiveness and aphasia. Head CT showed nonspecific findings consistent with neurotoxicity from recent CAR T-cell therapy. Treatment with dexamethasone was initiated. On day 2 of admission, quetiapine and dexmedetomidine were started for agitation. She worsened clinically on day 3 and was transitioned to high-dose IV methylprednisolone. The child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP) C-L team was consulted for uncontrolled episodes of agitation and risk for unintentional self-harm. Quetiapine was changed to olanzapine and melatonin was started for sleep. On day 7, a clonidine transdermal patch was placed and diazepam was given for additional agitation unresponsive to dexmedetomidine boluses. On day 8, the CAP C-L team recommended increasing her nighttime dose of olanzapine and scheduling morning and afternoon doses of olanzapine. On day 10, the patient was able to answer questions with slurred one word responses. On day 12, dexmedetomidine was discontinued. Oral clonidine was scheduled and transdermal clonidine was increased. The patient began speaking in short phrases and was able to ask simple questions. Episodes of agitation and need for PRN medications decreased. Prior to discharge, oral clonidine was discontinued, as was morning and midday olanzapine. Language remained impaired at discharge.

Discussion: Although the presentation and course of ICANS secondary to CAR T-cell therapy is well-documented, the concurrent psychiatric symptoms remain poorly understood. In this case, the utilization of quetiapine for initial management of agitation secondary to ICANS was minimally effective, but the patient’s agitation improved after switching to olanzapine. Clonidine was added for its efficacy in treating agitation in the pediatric population (3). Given continued intermittent agitation, her olanzapine was increased to twice daily. She subsequently showed marked improvement in her agitation and confusion. We believe these two medications largely contributed to her positive behavioral outcome and should be considered in other patients struggling with acute agitation secondary to ICANS.

References:

Pehlivan KC, Duncan BB, Lee DW. Car-T cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Transforming the treatment of relapsed and refractory disease. Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports. 2018;13(5):396-406. doi:10.1007/s11899-018-0470-x

Hayden PJ, Roddie C, Bader P, et al. Management of adults and children receiving car T-Cell therapy: 2021 best practice recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (Jacie) and the European Haematology Association (EHA). Annals of Oncology. 2022;33(3):259-275. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.12.003

Marzullo LR. Pharmacologic management of the agitated child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014 Apr;30(4):269-75; quiz 276-8. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000112. PMID: 24694885.