Collaborative and Integrated Care

Session: Poster Session

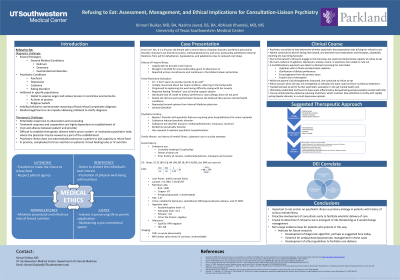

(053) Refusing to Eat: Assessment, Management, and Ethical Implications for C-L Psychiatry

Trainee Involvement: Yes

Kinnari Ruikar, MD

Resident Physician

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Dallas, Texas, United States.jpg)

Abhisek Khandai, MD, MS

Assistant Professor

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Dallas, Texas, United States

Nashra Javed, n/a

Medical Student

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Dallas, Texas, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

Introduction: Patients who refuse to eat present unique diagnostic, therapeutic, and ethical conundrums for inpatient general medical teams. We discuss the role of the consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatrist in evaluating psychiatric and general medical causes for refusal to eat, as well as the importance of liaison beyond diagnosis and decisional capacity assessment, particularly for patients within marginalized populations.

Case Description: Ms. X is a 29-year-old Black female with a history of bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, stimulant use disorder, and sinus tachycardia admitted from jail for dehydration, hypokalemia, and palpitations due to reduced oral intake. While Ms. X initially permitted administration of IV fluids and electrolytes, she refused to engage in the interview and declined most medications and therapies. Psychiatry was consulted to help determine whether psychiatric decompensation was driving her refusal to eat; however, the patient continued to decline being interviewed, repeatedly claiming she was being harassed. The patient did not appear agitated, depressed, anxious, manic, or psychotic, stymying psychiatric diagnosis. A multidisciplinary and atheoretical approach was taken to attempt increasing her oral intake, including an empiric trial of olanzapine, hydration and electrolyte repletion, clarification of dietary preferences, and encouragement from providers. While her lab derangements improved, she continued to refuse to eat, prompting an Ethics consultation regarding forced nutrition. Due to the patient’s refusal to engage in the interview, she could not demonstrate capacity to refuse to eat. However, as she was not emergently ill, ethically the primary team could not force nutritional treatment. Ultimately, the patient was deemed medically stable, and transferred back to jail for further psychiatric evaluation.

Discussion: Refusal to eat can stem from several etiologies, including psychiatric illness, general medical or cognitive illness, or volitionally in incarcerated patients as a method of expressing their restricted autonomy (1,3,4). It is well established that incarcerated patients also have a higher prevalence of mental illness, and disproportionately come from minoritized and low socioeconomic status communities, thus increasing their structural vulnerability (2). The C-L psychiatrist can help primary teams avoid anchoring on psychiatric illness and develop multidisciplinary plans to address behavioral concerns, whilst advocating for ethical care for patients from marginalized populations.

References:

1. Brockman B. (1999). Food refusal in prisoners: a communication or a method of self-killing? The role of the psychiatrist and resulting ethical challenges. Journal of medical ethics, 25(6), 451–456. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.25.6.451

2. Gómez-Figueroa, H., & Camino-Proaño, A. (2022). Mental and behavioral disorders in the prison context. Revista espanola de sanidad penitenciaria, 24(2), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.18176/resp.00052

3. Larkin E. P. (1991). Food refusal in prison. Medicine, science, and the law, 31(1), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580249103100108

4. Nagahama, Y., Ito, T., Fujishiro, H., Akutagawa, H., Okabe, M., Ohtaki, H., Tsukada, S., & Fukui, T. (2022). Outcome of therapeutic interventions against food refusal in patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics: the official journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, 22(1), 156–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12769