Cardiology

Session: Poster Session

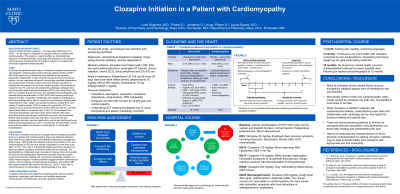

(004) Clozapine Initiation in a Patient with Cardiomyopathy

Trainee Involvement: Yes

Luke Klugherz, MD, PharmD

Resident Physician

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Laura Suarez, MD

Psychiatrist

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota, United States- JL

Jonathan G. Leung, PharmD

Pharmacist

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

Background/Significance: There is limited literature guidance – one case report (Sanchez et al., 2016) – on the usage of clozapine for psychotic illness in patients with cardiomyopathy. We present a case that offers an interdisciplinary approach involving psychiatry, cardiology, and pharmacy in the decision-making process and monitoring of clozapine initiation in a patient with previously diagnosed cardiomyopathy. Conclusion/Implications: In patients with previously diagnosed cardiomyopathy, liaison between psychiatry, cardiology, and pharmacy can facilitate appropriate cardiovascular risk stratification and safe clozapine initiation. References C. U. Correll, et al. A Guideline and Checklist for Initiating and Managing Clozapine Treatment in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. Jul 2022.

Case: A 35-year-old gentleman with history of treatment-resistant schizophrenia and idiopathic cardiomyopathy (left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) 29% three years prior to admission) was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric hospital after 1 week of worsening psychosis and functional decline. He was reportedly adherent to long-acting injectable paliperidone and perphenazine. Previous electroconvulsive therapy caused sinus bradycardia and pause, and his known cardiomyopathy had precluded a clozapine trial. His case was discussed with cardiology colleagues who recommended baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) (sinus arrhythmia; QTc 450 ms), baseline troponin (normal), and repeating echocardiography; this showed interval normalization of LVEF (54%) with normal systolic and diastolic function. Clozapine monotherapy was initiated. Cardiology and pharmacy assisted with a plan to monitor for cardiotoxicity including daily assessment of vitals, weight, and cardiac symptoms, weekly ECG, and weekly C-reactive protein (CRP) to screen for myocarditis. ECG on clozapine day 4 showed normal sinus rhythm with QTc 436 ms, and CRP was unremarkable on clozapine days 12 and 19. He developed mild orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia which resolved after dose reductions of previous lisinopril, metoprolol succinate, and furosemide. Steady-state clozapine level was 353 ng/mL. His psychosis and independent function improved significantly, and he was discharged home. Repeat echocardiography at 6 and 12 months was recommended. He was psychiatrically stable and showed no cardiotoxicity 4 months after hospitalization.

Discussion: In this case, clozapine was used to manage treatment-resistant psychotic illness in a patient with cardiomyopathy. Previously deferred clozapine trials likely led to polypharmacy and suboptimal psychosis management. Siskind et al., 2020 found that clozapine-induced myocarditis (0.7%) and cardiomyopathy (0.6%) are rare, though myocarditis is more likely to be fatal (12.7%). The risks of suboptimally treated psychosis needed to be balanced against clozapine-associated cardiovascular sequelae. The interdisciplinary collaboration was necessary to discuss risks and benefits; his interval echocardiographic improvement implied improved cardiac reserve and reduced mortality risk. Having this knowledge enabled us to jointly initiate clozapine. Recent guidelines suggest baseline cardiovascular studies, daily monitoring of cardiovascular symptoms, and weekly CRP and troponin tests for two months (Correll et al., 2022). There was no interval evidence of myocarditis or cardiomyopathy in our case.

A. Y. Sanchez, et al. Clozapine in a patient with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a case report. BJPsych Open. Nov 2016.

D. Siskind, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of rates of clozapine-associated myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. May 2020.