Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Session: Poster Session

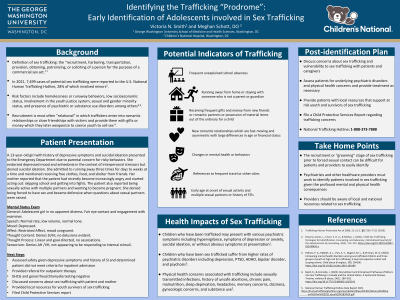

(041) Identifying the Trafficking "Prodrome": Early Identification of Adolescents Involved in Sex Trafficking

Trainee Involvement: Yes

- VS

Victoria N. Smith

Medical Student

George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Washington, District of Columbia, United States

Meghan Schott, DO FAPA

Medical Director of Psychiatric Emergency Services

Children's National

Washington, District of Columbia, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

1. Browne-James, L., Litam, S. D. A., & McRae, L. (2021). Child Sex Trafficking: Strategies for Identification, Counseling, and Advocacy. International journal for the advancement of counseling, 43(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-020-09420-y 2. Palines, P. A., Rabbitt, A. L., Pan, A. Y., Nugent, M. L., & Ehrman, W. G. (2020). Comparing mental health disorders among sex trafficked children and three groups of youth at high-risk for trafficking: A dual retrospective cohort and scoping review. Child abuse & neglect, 100, 104196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104196 3. Baird, K., & Connolly, J. (2023). Recruitment and Entrapment Pathways of Minors into Sex Trafficking in Canada and the United States: A Systematic Review. Trauma, violence & abuse, 24(1), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211025241 4. (2022, November 15) National Human Trafficking Hotline Data Report 2021. Humantraffickinghotline.org. Retrieved March 29, 2023 from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/National%20Report%20For%202021.docx%20%283%29.pdf

Background: In 2021, 7,499 cases of potential sex trafficking were reported to the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline, 28% of which involved minors4. Children who have been sex trafficked suffer from higher rates of psychiatric disorders including depression, PTSD, ADHD, bipolar disorder, and psychosis2. Risk factors increasing entry into sex trafficking include homelessness or runaway behaviors, low socioeconomic status, and presence of psychiatric or substance use disorders among others2,3. Recruitment is most often “relational” in which traffickers enter into romantic relationships or close friendships with victims and provide them with gifts or money which they later weaponize to coerce youth to sell sex3.

Case: A 13-year-old girl with history of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation presented due to parental concern for risky behaviors. She endorsed depressed mood and anhedonia in the context of interpersonal stressors but denied suicidal ideation. She admitted to running away three times for days to weeks at a time and mentioned receiving free clothes, food, and shelter from friends. Mom reported that the patient had recently become increasingly angry and started acting out: skipping school, getting into fights, and running away from home. The patient also reported being sexually active with multiple partners and wanting to become pregnant, however sexually transmitted illness (STI) and urine pregnancy testing were negative. She denied being forced to have sex and became defensive when questions were raised about sexual partners and the location of where she lives when not at home.

Discussion: Sex trafficking is rarely disclosed by the victim and hence it can be difficult to readily identify the “grooming” or prodromal stages. Given the positive attention and material benefits of the grooming stage, coupled with a lack of emotional maturity and life experience, youth are even more unlikely to report concerns in early signs of sex trafficking. In this case, our patient was adamant that she was not being sex trafficked because she denied forced sexual activity. Providers unfamiliar with the grooming stages of trafficking may miss opportunities for early intervention.

Conclusions: Sex trafficking may be difficult for patients and psychiatric providers to identify in the grooming stage. Psychiatrists must be able to identify early stages of trafficking to intervene and mitigate associated psychiatric consequences.

References: